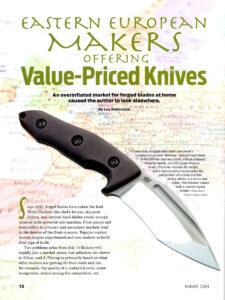

We thought you might enjoy a recent article written by Mike Haskew in January 2020 on BladeMagazine.com, “7 Tips for Buying Custom Knives.”

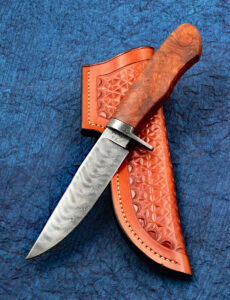

Les Robertson said many custom knife buyers/collectors make the mistake of overlooking a maker’s skill level, quality, customer service, and/or delivery issues because the knife can be sold immediately for a profit. The presentation Bastion Dagger by Tim Steingass features an armor-piercing tip. (SharpByCoop knife image)

1) Know the Trends

“This has got to be through the old way of human contact,” Bob Loveless knife specialist John Denton observed, “sort of like the lunchroom in school. You hang out, listen, see what is moving, what dealers are buying and, of course, now with the ‘inter-web,’ we have so much more information within seconds, while in the ’70s or ’80s we had to wait for BLADE® Magazine or the gun magazines to run stories on Loveless.

“Shows are still important to attend, but nowhere like they were years ago. Face to face is still part of the knife world.”

2) Maker Charisma

A lot depends on whether the maker has the kind of personality that appeals to the knife enthusiast. At Blade Gallery, Daniel O’Malley specializes in one-of-a-kind custom knives. The answer includes multiple factors.

“There are a lot of things that go into making a knifemaker’s knives ‘hot,’” he reasoned. “Part of it is the personality of the maker. When a collector meets a maker for the first time, the collector often has a picture in his head of what the maker will be like. If the maker falls short [of the collector’s expectations], it can be quite disillusioning.”

3) Customer Service

“[The maker] being willing to repair knives when there is a problem is also very important,” O’Malley continued. “It can easily make the difference in a collector continuing to purchase a maker’s work. It can even be the difference in whether a person continues to collect the maker’s knives over time.

“After all, if a collector has spent a large sum of money on their collection, it can be very nerve wracking to find that it’s hard to get a damaged knife repaired. Similarly, it can be comforting if a problem can be relatively painlessly solved.”

4) Do Your Homework

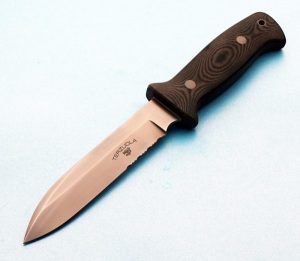

Les Robertson of Robertson’s Custom Cutlery offers custom fixed blade and folding knives, including tacticals and presentation pieces, as well as some exclusives. His take on the delicate topic of a maker’s reliability and the quality of the maker’s work is sage advice for knife enthusiasts in any price range or level of experience.

“I give my client the very best information I have at the time,” Robertson asserted. “This includes issues with a maker or the quality of their work. Often, a maker’s skill level, quality, customer service, and/or delivery issues are overlooked because the knife can be sold immediately for a profit.

“Given the prices of many of the custom knives today, I highly recommend that collectors do their homework before purchasing a knife.

“I realize this takes away from the thrill of instant gratification and removes some of the fun out of the hobby. Long term, though, you will feel great about every knife you have bought, and your wallet will thank you.”

Purveyor John Denton said he turned down $60,000 at the 2014 BLADE Show for this Big Bear in sheep horn and Dan Wilkerson engraving. (Point Seven knife image)

5) Set An Allowance

Everyone, it seems, has spending limits. The role of the dealer often involves assisting clients in determining how much to spend. Recognition of the amount of disposable income available keeps a buyer/collector in the game.

6) Collect With A Purpose

Denton advises customers to acquire some knowledge on prices and to assess their real purpose for buying custom knives in the first place.

“First of all, you want collectors to be educated,” he commented, “and not to be buying just to make money. That is the riskiest way to approach collecting. But then if they buy what they like and in three years can’t get 10 cents on the dollar, it will cut their knife buying down and drive them out of the market.”

Dealer Dave Ellis notes that the investment perspective differs greatly from that of the collector who wants to enjoy, build and retain knives for years to come.

“When I chat with newbies,” he remarked, “a lot of them get into knives from an investment standpoint. They have read in the Wall Street Journal that investing in knives is a good idea, or heard about a knife that was purchased for $800 and then sold for $8,000. I tell them to buy what they like first and to worry about resale later because if it doesn’t pan out, then they won’t have to hold onto something they don’t like.”

Taking a measured approach is key to successful, price-sensitive acquisitions.

“I tell the collector to pace themselves,” Denton said. “Get into a knife that will be easy to turn if you get tired of it down the road. I’ve had several people ask me to build them a $300,000 collection, and I tell them I don’t do that because they will get mad if they don’t make 14 percent growth per year—and they don’t know why they’re buying the knife.

“The true collector has studied the knives and the market, and he will realize what knives are worth and what he can resell them for.”

Those who are new to the custom knife market can tap a great resource in a top dealer. Advice on the market, prevailing prices and hot makers is only part of the relationship. High-end folders by BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame® member Ron Lake, Warren Osborne and Jim Martin, along with Loveless fixed blades, are among Ellis’s offerings.

When Dave talks with a new buyer/collector, he asks a few basic questions.

“There are more heavy hitters getting in the game with lots of money,” he said, “but that doesn’t mean they are buying the right things. What have their interests been up to now? Did they grow up with knives? Do they carry and use a knife? What is their reason for buying now? Use it? Collect it? Give it to a nephew for college graduation? I don’t want to offer a $7,000 Loveless hunter when a $150 skinner by any smith will do.”

7) Attend Shows That Fit

Though knife shows may be one of many ways to gain information and see what is out there, the individual contact with dealers, makers and other knife enthusiasts is invaluable. Attending shows that mean the most to the individual buyer’s needs and wants helps in the education process and in finding the people and knives that enhance the experience.

Robertson attends the BLADE Show due directly to its diversity of custom knives for sale. He says that the Arkansas Custom Knife Show is also one of the premier forged blade shows and features apprentice, journeyman and master smiths in the American Bladesmith Society.

“The New York Custom Knife Show offers a variety of knives from very well-known custom knifemakers,” Robertson added. “This show in recent years has had more of a tactical knife flavor. The USN Show offers the widest variety of tactical folders you will see at any show in the world.”

These are just a few of Robertson’s picks. Other shows are out there, and many of them are quite beneficial to knife enthusiasts looking for certain styles of knives and/or makers.

Sign up for our Newsletter.

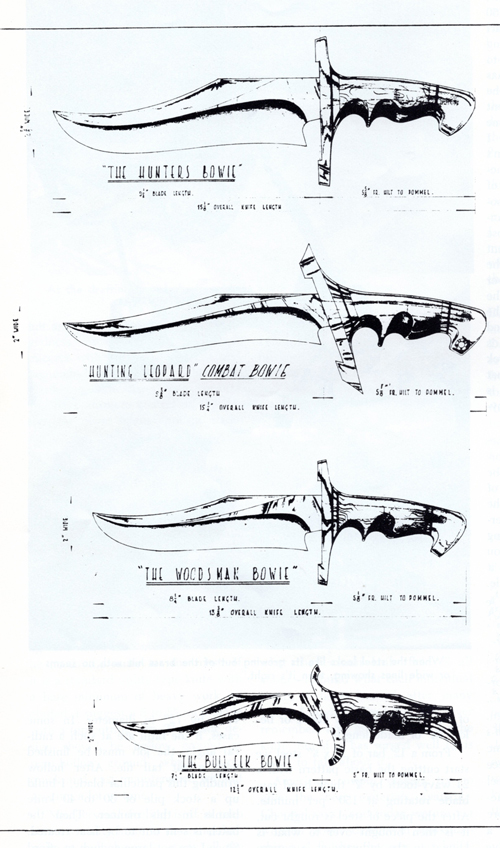

Robertson’s Custom Cutlery is your source for custom knives from today’s leading custom knife makers. We only feature the highest quality knives at value prices. Our custom fixed and folding knife selection includes tactical fixed and folding knives, presentation fixed and folding knives, bowies, hunters and skinners, and a large selection of forged blades. Les Robertson, author and owner of Robertson’s Custom Cutlery, is also a Field Editor for Blade Magazine and an instructor at Blade University. If you have questions about the content in this article or about any knife or maker on our website, you can contact Les directly at customknives@comcast.net or (706) 650-0252.